Panasonic Lumix TZ70 / ZS50 review

-

-

Written by Gordon Laing

Intro

The Panasonic Lumix TZ70, or ZS50 as it’s known in North America, is the latest version of the company’s hugely popular travel zoom camera. Announced in January 2015, it once again comes exactly one year after its predecessor, the best-selling TZ60 / ZS40, and like that model the TZ70 / ZS50 becomes the first of the new crop of pocket super-zooms to reach the market.

The most important specification of any super-zoom camera is its optical range. The TZ70 / ZS50 inherits its predecessor’s 30x / 24-720mm equivalent zoom, continuing Panasonic’s tradition of keeping the same lens for two generations. Interestingly after steadily pushing sensor resolutions upwards though, Panasonic’s opted for a reduction from 18 Megapixels to 12 here, possibly using the same sensor as the earlier TZ25 / ZS15. While the sensor size remains the small 1/2.3in size, the lower resolution should hopefully improve the image quality.

As before, the specification which sets the flagship Lumix travel-zoom from its rivals is the inclusion of a built-in electronic viewfinder. I’m pleased to report Panasonic has upgraded the viewfinder resolution from 200k dot to 1160k dot, and while the 0.2in size is the same relatively small size, there’s a considerable boost in visible detail. Sadly there’s still no touch-screen, but there’s still built-in Wifi, NFC and support for RAW files. Interestingly the built-in GPS receiver of its predecessor has been removed, but it’s possible to record a GPS log with your smartphone and sync it over Wifi like other Lumix cameras. As usual Panasonic also offers a lower-end version, the TZ57, which sports a 20x zoom, 16 Megapixels and a 180 degree tiltable screen, a capability the TZ70 / ZS50 lacks. So Panasonic’s now played its hand and the big news for the flagship TZ is the higher resolution EVF. Today Canon also announced the SX710 HS, which will be one of the main rivals to the TZ70 / ZS50; it’s almost identical to its predecessor other than increasing the resolution from 16 to 20 Megapixels, proving the two companies are heading in opposite directions here. So which is best? To find out I tested the Lumix TZ70 / ZS50 alongside Canon’s SX710 HS and in my full review you’ll find out the pros and cons of both and ultimately which will be the best 30x pocket super-zoom for you!

Panasonic Lumix TZ70 / ZS50 design

The Lumix TZ70 / ZS50 shares almost exactly the same design and control layout as its predecessor, and has the same dimensions too at 111x64x34.4mm and weighing 243g including battery. The two physical differences are a slightly restyled top panel and a considerably chunkier grip. Both are beneficial. The upper surface remains a couple of milllimeters taller at the viewfinder end, but on the older model, dipped down straight after the viewfinder housing. On the new TZ70 / ZS50, it doesn’t dip down until it reaches the mode dial, which actually reduces the chance of it being turned by mistake when being pulled out of a pocket – a small but nice design tweak. The benefit of the bigger grip is more obvious – on the older TZ60 / ZS40 there was little more than a short bar on the front to hold onto, but now Panasonic has fitted a more substantial rubber grip. Don’t get me wrong, it’s still obviously quite small, but it’s a considerable improvement over the older arrangement. Any improvement is welcomed as handholding a camera this small at an equivalent of 720mm is no mean feat.

|

Looking at the competition, Sony’s Cyber-shot HX60V measures 108x64x38.3mm and 272g including battery, while Canon’s PowerShot SX710 HS measures 113x66x34.8mm and weighs 269g including battery (the same as its predecessor). This makes all three 30x travel zoom rivals very similar in size and weight, although both the Panasonic and the Canon are thinner than the Sony.

On the top surface the TZ70 / ZS50 has a minor bulge to accommodate the viewfinder housing alongside stereo microphones, a raised but fairly stiff mode dial, generously sized shutter release with zoom collar, and two buttons, one lozenge shaped for power and the other a red record button to start filming video in any mode. Unlike the Sony HX60V and Canon SX710 HS which both have popup flashes, the Lumix TZ70 / ZS50 has its flash built-into the front surface making it available without an additional press. The Sony HX60V is the only one of the three to feature a hotshoe.

The TZ70 / ZS50 shares the same controls as its predecessor, including two customizable dials, one around the lens barrel which turns smoothly, and one on the rear, a thumb-operated wheel which clicks when turned; this rear wheel also tilts in four directions to deliver the traditional cross-key navigation, more of which in a moment.

You can customize the functions of either control wheel, or have the camera assign them as it sees fit. You may want to customize them though as with the default settings, both wheels often perform exactly the same function, for example, both adjusting the aperture or shutter in their respective priority modes. This seems a bit daft when one should really adjust, say, the exposure compensation instead by default. You can easily reconfigure one to adjust exposure compensation, but then when you enter manual mode, that dial effectively becomes redundant, when what you’d really want to happen is the default option where one operates the shutter and the other adjusts the aperture as you’d expect. I couldn’t find a way to enjoy both scenarios without reconfiguring the dials back and forth – something which also frustrated me on the old model.

Like earlier Panasonic cameras, there’s also the on-screen Q-menu which offers quick access to a variety of settings. Like its predecessor, the TZ70 / ZS50’s Q-menu employs a row of settings along the bottom of the screen which popout their options onto a curved section of a circle. You use the left and right cross keys to select the desired setting (in Program mode consisting of the aspect ratio, resolution, ISO, white balance, AF area, video quality and screen brightness), then use either dial to adjust it. Yep, once again both dials doing the same thing when one could have scrolled through the settings and the other make the actual adjustments.

In addition, pushing up, down, left and right on the rocker dial gives you immediate access to exposure compensation, drive mode, AF mode and flash mode. There’s also two customizable Function keys to give quick access to other settings, such as image compression, metering, and various on-screen guides, although sadly still not ISO. To change the sensitivity you either have to go through the Q.Menu, the main menu or assign the function to one of the two dials.

What you still won’t be doing on the TZ70 / ZS50 though is touching the screen to make any adjustments. Panasonic decided to dump the touchscreen on the earlier TZ60 / ZS40 and sadly has not resinstaed it here. I think this is a shame as it was a key differentiator with those models and allowed you to quickly and easily set a focusing area by just tapping it. Alas not possible on the TZ70 / ZS50, although to be fair equally not possible on the HX60V or SX710 HS either.

The TZ70 / ZS50 is powered by a 1250mAh Lithium ion battery pack, the DMW-BCM13E, quoted as being good for 300 shots per charge, compared to 380 on the Sony HX60V and 230 on the Canon S710 HS. These figures may be under CIPA conditions, but none take into account any Wifi activity or movie recording, so I’d take them with a pinch of salt. Certainly I found it easy to run any of them down during a day of fairly active photography, so you should keep an eye on the battery life.

On the upside, the TZ70 / ZS50, like its predecessor and the Sony HX60V, recharges its battery in-camera over USB. I realize people are divided over in-camera USB charging versus mains charging in a separate unit, but I’m definitely a supporter of the former, especially for a point-and-shoot camera. This is not a higher-end DSLR or mirrorless camera where many people carry a spare and prefer to keep their camera operational while a battery is charging. On a point-and-shoot camera, most people only ever have one battery and simply want to top-it-up as easily as possible. With a mains charger you need to remember to take the unit with you on trips and find a mains outlet to plug it into. With in-camera USB charging, all you need is the cable then you can simply connect it to a laptop, a portable battery, an in-car adapter, or any USB mains adapter you probably already have with you for another device, such as a phone or tablet. I love being able to topup the charge while I’m driving between locations without needing any special kit, and have also recharged on buses, planes or other vehicles equipped with USB ports. I’m also a big fan of portable USB batteries which can top-up a USB-powered device like the TZ70 / ZS50 wherever you may be; I use an Anker Astro Mini battery which is also perfect for topping-up a phone or tablet that’s flagging. Ultimately I believe USB charging is definitely the preferred solution for a camera that’s designed for travel.

Staying on the subject of ports, the other wired connector on the TZ70 / ZS50 is micro HDMI. The camera additionally features built-in Wifi with NFC to aid negotiation on compatible devices, although the GPS receiver of its predecessor has sadly been removed. I’ll talk more about Wifi later in the review, but for now mention that the Sony HX60V has both Wifi and GPS built-in, but the Canon SX710 HS only has Wifi – so like the Lumix, relies on a separate handset to make a GPS log for subsequent syncing.

Panasonic Lumix TZ70 / ZS50 screen and viewfinder

The Lumix TZ70 / ZS50 is equipped with a 3in screen with 920k dot resolution and 3:2 shape. As noted earlier, it’s not touch-sensitive, a decision I believe made to hit a lower price point. Certainly the absence of a touch-screen hasn’t hurt sales of Sony’s or Canon’s pocket travel zoom cameras, so maybe Panasonic wonders why it should fit an expensive component when no-one else does. But that’s exactly the reason it should continue in my view. Not only is a touch-screen an invaluable aid for selecting AF areas or entering text, but it was a key differentiator for the flagship Lumix travel zoom. I know some people aren’t bothered about them, but I personally missed it on the older TZ60 / ZS40 and continue to miss it on the new model.

So in terms of screen composition, the TZ70 / ZS50 is very similar to its two main rivals, with the same size display and resolution. But there is a very important difference between them when it comes to an alternative means of composition. The Lumix TZ70 / ZS50 is the only one to squeeze in an electronic viewfinder, impressively without resulting in a body that’s noticeably bigger.

While the viewfinder was introduced on the earlier TZ60 / ZS40, the new model improves on it in two respects. First, the panel may remain small at 0.2in, but the resolution has increased significantly from 200k dot to 1166k dot, allowing it to avoid the coarse image of its predecessor and deliver considerably finer detail. It’s still a world apart from the large and even more detailed viewfinders we’re seeing on the latest mirrorless system cameras, or even Sony’s RX100 III and not something you look through and exclaim ‘wow’. But it remains a very useful tool, not only when shooting under direct sunlight which renders most screens unusable, but also to hold the camera steadier when shooting or filming at very long focal lengths; holding a camera to your eye provides a third point of contact and greatly reduces potential shake. The second upgrade over its predecessor is the presence of an eye sensor. Previously you needed to press a button to switch between the screen and viewfinder, but now a new sensor does it for you, which greatly improves the usability. Meanwhile the old LVF button remains, but now doubles-up as a second Function button.

In the absence of a touch-screen, the viewfinder remains the key differentiator between the TZ70 / ZS50 and its rivals. Neither the HX60V nor SX710 HS have built-in viewfinders, and while the Sony can accommodate a considerably nicer one as an optional accessory using its hotshoe, it is a large and expensive option which I suspect most owners won’t bother with. The key benefit of the viewfinder on the TZ70 / ZS50 is it’s built-in, always with you, and doesn’t compromise the size of the camera compared to rivals. It’s small, but very useful.

A few notes on the display views. The TZ70 / ZS50 offers a variety of views with varying amounts of information and guides. There’s a dual-axis leveling gauge, and if enabled in the menus, a live histogram or choice of guidelines. Annoyingly the TZ70 / ZS50 still won’t rotate portrait shaped images in playback to fill the screen when the camera is turned on its side either. This is a daft decision which continues to be replicated on Lumix cameras. Please Panasonic, follow everyone else and rotate your images to fill the screen during playback!

Panasonic Lumix TZ70 / ZS50 lens

The lens range is the most important specification on a super-zoom camera, and following Panasonic’s strategy of using the same range for two generations, the TZ70 / ZS50 shares the same optical specs as its predecessor. So the Lumix TZ70 / ZS50 sports the same 30x zoom as the TZ60 / ZS40, equivalent to 24-720mm in 35mm terms. This range matches the Sony HX60V, and is essentially the same as the 25-750mm range delivered by the Canon SX710 HS. The focal ratios are similar too, with the Panasonic, Sony and Canon starting off at f3.3, f3.5 and f3.2 at the wide-end respectively, and ending at f6.4, f6.3 and f6.9 respectively at the long end. The closest focusing distances with the lenses set to wide are 3cm, 5cm and 1cm respectively, allowing all to capture good macro images, although giving the Canon the overall edge.

So what does a range of 24-720mm let you capture? Below are two photos taken from the same position with the TZ70 / ZS50 using each ends of the zoom, illustrating the range at your disposal – at one moment capturing a wide field before getting very close to distant details the next. It’s extremely flexible, and while you need to take care for camera shake at the long end, especially with the much reduced aperture, the stabilisation is excellent and again there’s the option to use the viewfinder for even greater stability.

Panasonic Lumix TZ70 / ZS50 coverage wide | Panasonic Lumix TZ70 / ZS50 coverage tele |

|  |

| 4.3-129mm at 4.3mm (24mm equivalent) | 4.3-129mm at 129mm (720mm equivalent) |

With a maximum optical focal length of 720mm on a body with a minimal grip, it’s very important to have effective image stabilisation. To put the OIS system to the test on the TZ70 / ZS50, I zoomed it into its maximum focal length and took a series of photos at progressively slower shutter speeds first without stabilisation, then with, to see what it was capable of ironing-out.

Panasonic Lumix TZ70 / ZS50 Image Stabilisation off / on | ||

|  | |

100% crop, 4.3-129mm at 129mm, 1/25, 800 ISO, IS off | 100% crop, 4.3-129mm at 129mm, 1/25, 800 ISO, IS on | |

On the conditions of the day I required a shutter speed of 1/400 to reliably handhold a shake-free image at 720mm, but with stabilisation enabled, I managed the same result at 1/25, corresponding to about four stops of compensation in practice – a valuable capability.

What this doesn’t illustrate though is how useful the stabilisation is when composing with the TZ60 / ZS40 at maximum zoom. With stabilisation disabled, I may have been able to handhold a sharp shot at around 1/400, but the image was dancing around the screen and almost impossible to line-up. Switch stabilisation on though and the composition became rock-steady, making it easy to line-it up exactly as desired. It’s an invaluable tool when packing such long focal lengths into such small bodies. I should also add that this test was performed when composing with the screen and as discussed earlier, you can enjoy steadier results when composing with the viewfinder held to your face – so it’s worth switching to the EVF when you’re shooting at the longest focal lengths or in low light.

Panasonic Lumix TZ70 / ZS50 movie mode

The Lumix TZ70 / ZS50 inherits most of the movie modes of its predecessor, allowing it to capture 1080p at 50p or 60p depending on region, and at a high rate of 28Mbit/s too.

While you can start recording in, say, Aperture Priority or Manual, don’t get too excited as exposures are fully automatic once you start filming. The only exception is when filming in the Intelligent Auto mode, where the TZ70 / ZS50 can choose from one of four scenes: portrait, landscape, macro and low light. Like earlier models, stabilisation is always active, even if you’ve disabled it for still photos. On the upside the optical stabilisation brings genuine benefits to the TZ70 / ZS50’s movie shooting as you’ll see in the clips below.Like the two models before it, audio is recorded in stereo from built-in microphones, and you can also zoom the lens while filming. As before you can start filming in any mode by simply pressing the red record button and you can also capture still photos while filming, albeit only in the 16:9 aspect ratio but at a usable resolution of 9 Megapixels – but watch out as there’s only a limited number you can take during a clip (indicated on-screen and normally around nine) and if you’re moving the camera at the time, they’ll almost certainly suffer from motion blur due to the slower shutter speeds typically implemented during video recording.

Panasonic continues to offer the choice of two encoding formats, AVCHD or MP4, with Panasonic recommending the former for the best quality results or playback on HDTVs, and the latter for extensive editing or uploading.

The AVCHD mode can record video in either 1080p at 28Mbit/s, or 1080i or 720p, both at a rate of 17Mbit/s. 1080p footage is recorded at 50p or 60p depending on region, while 1080i footage is recorded at 50i or 60i depending on region. 720p footage is recorded at 50p or 60p depending on region. You can choose to tag AVCHD movies with GPS location data, although it may cause incompatibilities with some devices. Using the best quality 1080p AVCHD mode, you’re looking at about 200Mbytes per minute of footage, considerably more than the 1080i and 720p AVCHD modes which consume closer to 120 Mbytes per minute of footage.

The MP4 mode can record video in Full HD 1080p, 720p or standard definition VGA, at rates of 20, 10 and 4 Mbit/s respectively. All three modes are encoded using progressive video at 25p or 30p depending on region.

Panasonic quotes both the AVCHD and MP4 modes as being restricted to clips with a maximum length of 29 minutes and 59 seconds. Finally, Panasonic recommends using an SD card rated at Class 4 or faster for recording movies.

If the camera was set to manual focus for stills, then it also applies to movies, as does the presence of focus peaking if enabled. In theory this should let you manually pull focus while filming while using peaking as a guide, but you need to turn the lens control ring round and round to make any significant adjustments so it’s not very practical. But on the upside, switching to manual focus at least means there’s no chance of the camera refocusing at an inopportune moment.

If you’re using the Lumix Image app on your smartphone or tablet, you can use its screen to reposition the AF area by touch; this also works while you’re filming, so while you can’t pull-focus by tapping the actual camera’s screen, you can do it by remote control via the app. I have an example of this below.

Now let’s check out a bunch of clips to show you what the camera is capable of.

| |

|---|---|

| |

|

| |

|---|---|

| |

|

| |

|---|---|

| |

|

| |

|---|---|

| |

|

| |

|---|---|

| |

|

| |

|---|---|

| |

|

| |

|---|---|

| |

|

| |

|---|---|

| |

|

| |

|---|---|

| |

|

| |

|---|---|

| |

|

Panasonic Lumix TZ70 / ZS50 shooting experience

It’s amazing how the small things can make a big difference. By equipping the TZ70 / ZS50 with a slightly larger grip and an eye sensor, it becomes much more usable than its predecessor. It’s easier and more comfortable to hold, which is important when you’re handholding a pocket camera at 720mm equivalent, and you’ll also find yourself using the viewfinder a lot more now there’s no need to manually switch it on and off. Just raise the camera to your eye and the viewfinder activates.

The viewfinder image may still be very small, but the extra detail over the previous model makes it a much nicer experience. I found myself shooting with the viewfinder a lot more on the TZ70 / ZS50 than the last model, and as such benefitting from the extra stability it provides. This is important, as while the bigger grip certainly improves handling, it’s still a challenge to hold a camera of this size steady at the long-end of the zoom. Composing with a viewfinder held to you eye gives you that valuable third point of contact, reducing shakes and allowing you to compose and hold a shot more steadily. The presence of a viewfinder really gives the TZ70 / ZS50 a big advantage over its rivals.

With the eye sensor effectively rendering the LVF button mostly redundant, it’s become a useful second function key, which coupled with the two control dials, gives you plenty of ways to quickly and easily adjust settings. But as noted earlier, it could have been better if settings that are redundant in some modes (like exposure compensation in manual) could be ignored. So you could configure one of the dials to adjust compensation in PAS modes, but in Manual it would revert to adjusting the shutter or aperture rather than not doing anything at all. It also seems odd to have two customizable function buttons, but not allowing either to directly access the ISO.

In terms of response, the TZ70 / ZS50 feels a lot like its predecessor, which ranks it as one of the better in its class. Under bright conditions, it’ll snap into focus pretty quickly at any focal length. As light levels decrease, the AF becomes less confident especially at longer focal lengths, but rather than hunt back and forth incessantly, the camera slows down and generally gets there.

As before there’s the chance to let the camera decide on an AF area, track a subject (human or non-human), or set a single AF area yourself. Unlike Canon’s SX710 HS, it’s possible to move the single AF area anywhere on the frame – something which could have been easier with a touch-screen, but at least you can still reposition it. You can manually focus the camera too, with an optional magnified view for stills, and peaking for stills or movies. In manual focus, the front dial is the default control for adjusting the focusing distance and to me it felt a bit slow, but at least it is possible to adjust and set the focus if desired.

The lens range gives the camera enormous compositional flexibility and I loved knowing I could fill the frame with distant subjects. It really makes you look at the World a different way, noticing interesting arrangements and patterns that are out of reach for most cameras, at leats without lugging very heavy lenses around.

| |||

|

The compromise to squeezing a big zoom range into a small body though is having a slow focal ratio and a tiny sensor behind it. Both contribute, with the lens’s actual focal length, to make it difficult to deliver shallow depth of field effects. If you’re shooting a portrait or wildlife composition, you’ll find it hard to blur the background significantly even at the longest focal lengths. The following two shots were taken at the camera’s longest focal length (720mm equivalent) with the maximum aperture, and even then the background isn’t that blurred – plus composing anything at 720mm can be tricky even with a viewfinder and decent stabilization.

| |||

|

The only way you’ll enjoy a really blurred background on the TZ70 / ZS50 is to get very close to your subject in a macro composition. With the subject very close, aperture wide open and the background as distant as possible, you will get some blurring as seen below, but again if you want portraits with blurred backgrounds, a pocket superzoom is not the camera for you.

|

I should also mention the large inherent depth of field, coupled with diffraction kicking-in at anything smaller than the maximum aperture renders much of the manual exposure controls redundant on a camera of this type. But it’s still nice to have full control over the shutter and aperture if only to ensure the exposure does as it’s told.

With this in mind, I generally shot in Program mode with the TZ70 / ZS50, letting Panasonic’s engineers choose the optimal aperture on quality grounds. If I opted for a different exposure mode, it was invariably to go for a specialist scene preset or the panorama mode. The latter remains a highlight here, capturing and assembling broad panoramic views with nothing more than a casual pan over the scene. Sony may have pioneered in-camera panoramas, but Panasonic has certainly caught up.

The ability to shoot RAW is also an interesting differentiator on the TZ70 / ZS50. The tiny sensor means you’re unlikely to be retrieving much lost shadow or highlight detail, but shooting in RAW does give you the opportunity to easily adjust the white balance or apply just the amount of sharpening and noise reduction you’re after. So while it’s not as useful as a camera with a bigger sensor, RAW remains a handy capability.

Action photography is something that can prove a challenge with the TZ70 / ZS50. The camera certainly isn’t short of continuous shooting options, but various limitations, coupled with continuous AF that can’t really track fast subjects rules it out for sports.

I thought switching from an 18 to a 12 Megapixel sensor may have allowed bigger or faster bursts, but in terms of continuous shooting the TZ70 / ZS50 performs a lot like its predecessor. The top speed at the full resolution remains 10fps, but locks the focus and only fires small bursts. In my tests I actually managed closer to 12fps, but only for a tiny burst of six frames, which means you really need to time it well to capture the action.

Dropping the speed to the 6fps mode supposedly allows autofocus. In my tests it delivered 14 shots in 2.55 seconds, for a speed of 5.5fps, before dropping to around 3fps. The slightly bigger burst at a lower speed certainly recorded a longer sequence, but two and a half seconds still ain’t a great deal and when I tried tracking even slow waterskiers, the camera’s AF found it hard to keep up – plus the lack of a live update made it hard to follow the action.

The 3fps mode captured 31 images in 9.87 seconds, a speed of 3.14fps, but too slow to be useful, plus again the continuous AF wasn’t convincing. Finally, there’s 40 and 60fps burst options at a reduced resolution and fixed focus, the former capturing 30 shots at 5 Megapixels in 0.72 seconds. This can be fun if the reduced resolution isn’t limiting and you can trigger the burst at exactly the right moment.

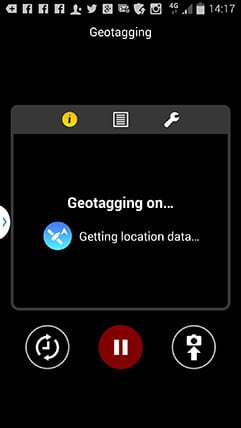

Moving onto wireless, Panasonic was one of the first camera companies to really embrace Wifi, so it’s not surprising to find a fairly mature solution on the TZ70 / ZS50. Wifi allows you to wirelessly copy images from the camera to your smartphone or tablet, or remote control it with a wide degree of manual adjustment.

On your handset you’ll see a live view of the image, along with the chance to drag a slider to adjust the zoom or tap an area to refocus on it. You can adjust the AF area and drive mode, and the exposure too. If the camera is in Manual, you can adjust the aperture and shutter separately and in program you can shift the suggested value. Buttons for the ISO and White Balance are also present, but like its predecessor, they remained greyed-out during my tests; I think they’re only unlocked on more advanced Lumix models like the G series. If you’re filming video, you can also use the screen on your handset to pull-focus by tapping; I have an example of this in my movie section above.

|  |  |

In playback you can view a series of thumbnails on your handset before deciding which you’d like to transfer – at the full resolution if desired. In use, it all works well, not to mention delivering a step-up over Canon on the SX710 HS, but for me Sony remains the leader in terms of a seamless Wifi experience. Depending on whether the camera is in composition or playback, a tap against an NFC-enabled handset will either launch the remote control or the image transfer function, regardless of how your Wifi is set up. No need to enable Wifi or start apps, Sony takes care of it all for you, whereas there’s still some manual intervention with Panasonic.

|  |  |

In terms of tagging images with positions, the older TZ60 / ZS40 sported a built-in GPS, complimented by a database of landmarks which popped-up on-screen. The latter was a key differentiator for the flagship TZ / ZS model for several generations, so it’s a bit of a shock to see it removed on the latest TZ70 / ZS50. That’s right, no more built-in GPS and no more database of landmarks.

| |||

|

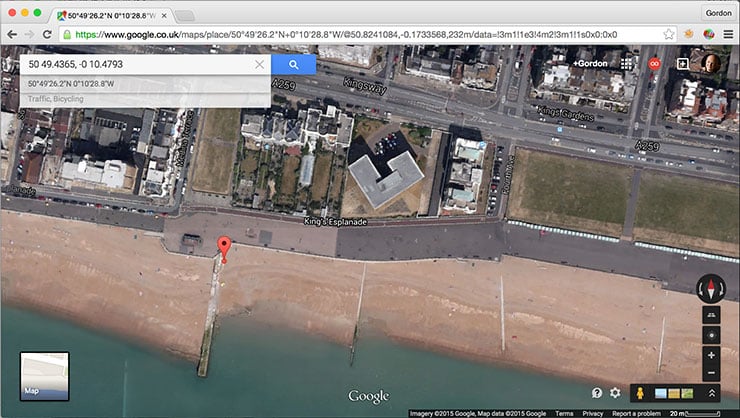

If you want the position embedded on your photos, you’ll need to use the Lumix app to sync with the camera, record a log, then apply it later; above is a photo where I embedded the GPS position, then entered the co-ordinates into Google Maps later. Compared to other GPS-logging solutions, the workflow here is pretty smooth but of course it’s nowhere as convenient as having the GPS built-into the camera itself. But with Canon pursuing the same strategy on the SX710 HS and Sony looking like it’s pulled out of this market (for now), it looks like GPS logging via an external device is the way forward.

Next check out the quality of the camera in practice, compared to Canon’s SX710 HS in my Lumix TZ70 / ZS50 quality results. Or head to my Lumix TZ70 / ZS50 sample images, or if you’ve seen enough, skip straight to my verdict!